用盡力氣在一起《插销》

文 王昱程(專案評論人)

sticking together: “EXIT”

By wang yucheng(column critic)

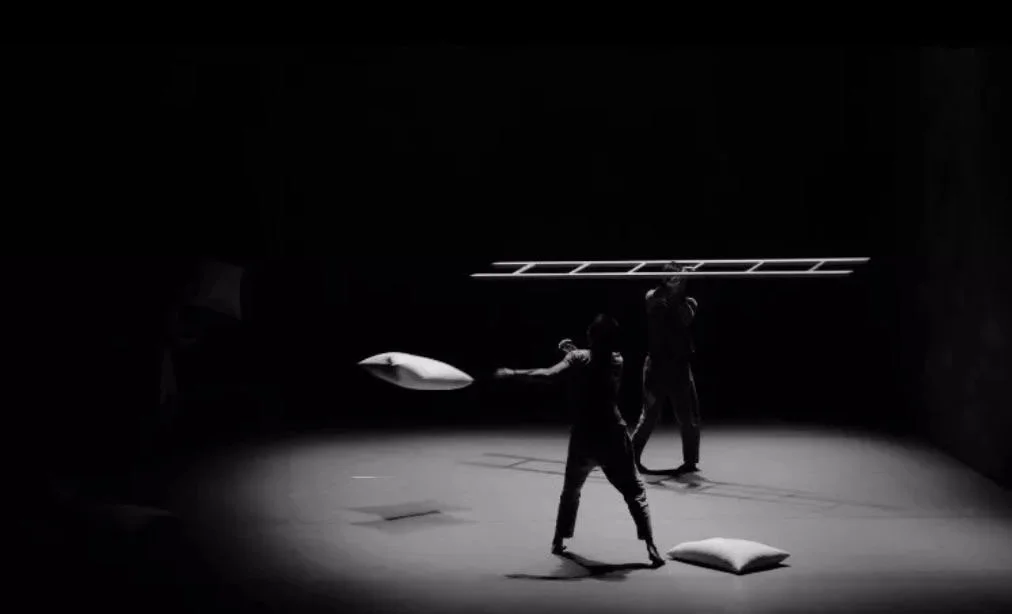

近來中國當代舞作品常出現在臺灣觀眾面前,光是今年,我們就看到了陶身體劇場讓物理空間與身體時間相作用,極簡卻不斷引發動覺衝動的《6》與《7》。楊朕的《少數民族》取樣民族舞蹈,反思統治技術與民眾渴望圖強的集體潛意識,刻劃出幽默與感性兼具的跨族群身體交流。不斷處於巨變中的中國,舞蹈半世紀以來從政府宣傳的工具轉變,漸成為個人創作、表達的型式,1987年廣東舞蹈學校開設四年制的現代舞大專班,現代舞蹈正式進入中國的高教系統,至此學院出身的舞者、編舞者輩出。《插銷》的編舞者古佳妮,1988年出生於四川,從小接受芭蕾舞、中國古典舞訓練,大學畢業後進入北京現代舞團,2012年起開始獨立創作,近期作品由活躍於中國與美國之間的乒乓策劃統籌巡演事宜,該組織同時也是陶身體劇場在世界巡迴的推手。作品《插銷》由臺灣的國家兩廳院與第18屆中國上海國際藝術節扶持青年藝術家計劃共同委託創作,2016年10月首演於上海當代藝術博物館,此次臺灣演出原本在宣傳片中出現的舞者李楠,則換成前陶身體劇場的舞者雷琰。走進劇場,見王宣淇一肩把雷琰扛起,倒插在枕頭堆裡,雷在空中彎舉的雙腿彷彿冬日枯枝,古佳妮則從灰牆後翻了出來,就這麼坐在牆上看著,王宣淇一個直衝正面倒下卻用右肩把身體撐起倒立半晌。勇敢、冷冽且肌力與技巧超凡,就是我對三位舞者的第一印象,灰色的L型高牆顯得密閉不透風,而填充蕎麥、重達七公斤的白色枕頭,或整齊疊放在牆邊,或幾坨幾坨地散布著。忽然之間,警鈴大作,沒有椅子的觀眾席階梯更彷彿在底下裝了馬達一般震動著,實在不免擔心整個劇場會就此爆炸。舞台上,閃光極速明滅,三位舞者竄也似地跑著,拋接枕頭,沉甸甸的枕頭從來飛不遠,啪地掉落在地上要滑也滑不動;於是笨重的物件對著無比靈活的身體,空氣中劇烈的噪音和震動的座席給我的焦慮不只存在於腦海,更在汗濕手心與輕微發麻的背脊。古佳妮從單肩撐起倒立的身體,雷琰和王瑄淇順其動勢,在強大的肌力支持下,古像是不倒翁一般被推來倒去,或是在站立時,古簡單用手進行水平面上的揮動,切割出空間的稜角,卻在雷與王的推動下形成一股炫風,不時牽動彼此急速旋轉。當古與王都用手臂和頭頂倒立成開場時枯枝一般的風景,雷開始一次扛起數個枕頭,在地平面用難以判別的邏輯,堆成棋盤格,看上去盡是寂靜,卻是藉由耗費大量體力的勞動所創造。從前作《左一右一》,古佳妮與李楠兩個人便展開了與日常物件互動的嘗試,使用鐵凳和長桌,以不尋常的姿勢支撐就能夠推來倒去。《插銷》在超乎日常經驗的沉重枕頭與間隔過長的單梯,顯得更加刺激危險。當王宣淇把高掛在牆上的單梯拿下來掛在頸上兀自旋轉,我在第一排座席渾身緊張不安,甚至可以感覺到梯子所颳起的陣風;或當雷踩在王與古舉起的單梯上,又鑽上鑽下,最後單靠頸項扣住梯子,被拖行在空間中。以頸項為支撐點,全身只鬆開膝關節,就這樣前傾後倒,或做頸項拋擲、承接、拖行、旋轉,幾乎成為舞作的標誌性動作。若從身體結構思考,頸部是整條脊椎被包覆最少的部位,神經、呼吸系統皆由此經過,受傷或是病變都十分危險;同時觸碰頸部容易讓人感到親密(或是被冒犯),按摩它更容易讓人放鬆,卸除戒備。古佳妮似乎有意剝去脖子本身所具有的文化意涵,純粹視之為物理的支點,卻在舞作過程中,諸般意象不斷襲向觀眾。讓我想到2017新人新視野黃于芬的舞作《緘默之所》以掐脖子發展動作的殺戮意象。《插銷》純粹利用身體和日常物件的物理性質發展動作主軸,卻產生種種怵目驚心的風景,把我拉往生命的幽暗之處,在緊迫連續的劇變裡,在讓人難以喘息的人際互動當中。或許,古佳妮的創作就如她所言,是花大半年在排練場上探尋、磨練。她們高超的技術除了發生在女體的強大肌力和默契十足的精密編排當中,更在於創造劇場中強烈的危機感,和連續無法歇止的事件中,迫使觀眾接收一份緊張焦慮,讓從日常物件發展的超乎現實舞蹈與觀眾的日常生活,也就是當下社會交織在一個動態的互動中。文化史學家弗格森曾說過:「現代性中唯一不變的因素就是運動的傾向,它的永久標誌。」變動的現代性體現在《插銷》的身體裡卻是疲於奔命,體力逐漸透支,每個創造後,毀滅便接踵而至,作用力與反作用力的物理定律其實就是因果循環,無法止息。美國舞蹈學者勒沛奇曾提出身體作為一種創造概念的哲學,不僅是一個獨立而封閉的實體,還是一個開放、動態的交換體系。也許由此思考十口無團所開展的身體風景更為有趣,當表演中發生的事件在表演者之間、表演者和觀眾之間造成一股迫近的張力,幾度凝滯,暫停的身體更激起存在狀態的時間感。不斷陷入暫時性,也就是海德格所說的「沉淪」,這描述動態性質的詞彙用來描述《插銷》顯得貼切,在一小時的舞作內完全耗盡氣力的勞動,從日常物件出發,原本意圖純粹操作物質之間的力學運動,變成超乎日常經驗的身體技藝,舞者在空間中運動,隨時間消耗體力,與屏息的觀眾緊密相連在一起。图 塔苏

Recently, Chinese contemporary dance works have often appeared in front of Taiwanese audiences. This year alone, we have seen Tao Dance Theater's "6" and "7", which combine physical space with time, revealing minimalism yet arousing impulses. Yang Zhen's "Ethnic Minorities" took a sample from ethnic dance, reflecting on the ruling class and the collective subconscious of people's desire to strive, and depicted cross-ethnic body communication with humor and sensibility. In a rapidly changing China, dance has become a form of individual creation and expression, rather than a tool of government propaganda as it was half a century ago. In 1987, Guangdong Dance School opened a four-year contemporary dance program, and contemporary dance officially entered China's higher education system. Since then, a large number of dancers and choreographers from academies have emerged.Gu Jiani, choreographer of “Exit”, was born in 1988 in Sichuan. Professionally trained in both ballet and Chinese classical dance, Gu joined Beijing Modern Dance Company after graduating from university. She began creating her own works since 2012. Her latest works are coordinated by Ping Pong Production, who is active in both China and the United States, and also promotes Tao' Dance Theater around the world. “Exit”, co-produced by Taiwan National Performing Arts Center—National Theater & Concert Hall, and the 18th Shanghai International Arts Festival “Raw” Program, premiered at Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art Theater in October 2016. In this performance in Taiwan, the original dancer Li Nan who appeared in the trailer was replaced by Lei Yan, former dancer of Tao Dance Theater.Walking into the theater, Wang Xuanqi carries Lei Yan on her shoulder and places him upside down in the pile of pillows. Lei's legs bend in the air looking like withered branches in winter, while Gu Jiani turns over from behind the gray wall and sits on the wall watching. Wang Xuanqi falls straight to the front and stands upside down with his right shoulder. Brave and apathetic, with extraordinary muscle strength and techniques, that was my first impression of the three dancers. The tall, gray, L-shaped walls are airtight, and the buckwheat-filled, seven-kilogram white pillows are stacked neatly against the walls or scattered in clumps. All of a sudden, the alarm goes off and the chairless auditorium steps vibrate as if they have motors installed underneath. I was afraid that the whole theater would explode. On the stage, the lights flash out and dancers begin running rapidly, tossing pillows around. The heavy pillows fall straight to the ground, without flying or sliding afar. The heavy objects are in strong contrast to the dancers’ extremely flexible bodies, and the anxiety brought by the intense noise in the air and the vibration of the seats exists not only in my brain, but also in my sweaty palms and slightly numb back.Gu pulls herself up from a single shoulder handstand position, with Lei and Wang using this motive, Gu is pulled back and force like a tumbler, showing great muscle strength. When standing, Gu swings her hands horizontally, cutting edges and corners of the space, and with the push of Lei and Wang, a dazzling wind is formed, causing each other to spin rapidly. While Gu and Wang both stand on their arms and heads to create the opening scene of withered branches, Lei begins carrying several pillows at a time, stacking them in a checkerboard pattern on the ground with unidentifiable logic, which looks like silence but is created by a lot of effort.Since previous work “Right & Left”, Gu Jiani and Li Nan have tried to interact with everyday objects, using iron benches and long tables that can be pushed back and forth with support in unusual positions. "Exit" is even more exciting and dangerous with unusually heavy pillows and a single ladder with too long intervals. I was on edge in the first row of seats and I could feel the wind blowing as Wang Xuanqi pulled down the single ladder from the wall and hung it around her necks spinning, or when Lei stepped on the ladder raised by Wang and Gu, and crept up and down, until at last she grasped the ladder by her neck and was dragged into space. With the neck being the supporter and the knee joints relaxed, dancers lean forward and backward, and the neck throws, catches, drags, spins, and this almost becomes the symbolic movement of dance. If we consider the body structure, the neck is the least covered of the whole spine, nerves and the respiratory system go through it, making it vulnerable to injuries and diseases. Touching the neck can be intimate (or offensive), and massaging it can be relaxing and disarming. Gu Jiani seems to deliberately strip away the cultural implications of the neck itself and considers it merely as a physical supporter, yet during the dance, such images constantly hit the audience. It reminds me of 2017 “new artist new vision” Huang Yufen's dance "The Place of Silence", in which the killing image is developed by strangling. “Exit” uses only physical nature of the body and everyday objects to develop the main axis of movement, but produces startling images that drag me into the darkness of life, the intense and continuous change, and the breathless interpersonal relationships.Perhaps, as Gu Jiani said, the creating process is to spend half a year in the rehearsal ground to explore and grind the work. The extraordinary effect of the dance requires not only great female muscle strength and precise choreography, but also a sense of crisis created in the theater, and the continuous and unstoppable events force the audience to receive a sense of anxiety, connecting the surreal dance developed from daily objects with everyday life, which dynamically interacts with the current society. As cultural historian Harvie Ferguson puts it: "The only constant in modernity is the tendency to movement, its permanent signature." The changing modernity reflected by “Exit” is that the body is always on the run, and the physical strength is gradually overdrawn. Every creation is followed by destruction, and the physical law of action and reaction is a cycle of cause and effect that cannot be stopped.Andre Lepecki, an American dance scholar, once proposed the philosophy of body as a creative concept, which is not only an independent and closed entity, but also an open and dynamic exchange system. Perhaps it is more interesting to think about the body scenery carried out by Untitled Group from this perspective. When events occur in a dance performance, it creates an imminent tension among performers, and between performers and the audience, and the stagnation and suspension of bodies arouse an existing sense of time. Falling into temporality (Heidegger's "Verfallen"), is an appropriate description of the dynamic nature of "Exit", during which the bodies exhaust in an hour’s dance. With daily objects in the dance, the law of movements intended for manipulating objects has developed into physical techniques beyond experience. Dancers move through space, expending energy over time, bonding with the breathless audience. photo by tasu